In brief:

- Scope 3 emissions account for up to 90% of food and beverage companies’ climate footprint.

- Agricultural co-ops and raw material suppliers are critical to turning corporate climate commitments into on-farm action and measurable reductions.

- Verified reductions are commercially valuable, but the sustainability claims marketplace is crowded and complex. Only credible, science-based claims will stand.

- Green premiums are emerging unevenly, and in many cases climate performance is becoming a baseline requirement rather than a bonus.

- Building credible chain of custody systems is the main bottleneck for scaling verified reductions, requiring strong data, recognized standards and supplier engagement.

- Farmers cannot carry transition costs on their own. Brands and buyers must co-invest to finance the shift to regenerative practices.

- Co-ops that act early and credibly can capture premiums, strengthen buyer relationships and secure a role in tomorrow’s low-carbon supply chains.

It’s difficult to think of any industry that is as vulnerable to the impacts of climate change than agriculture. Droughts, floods and extreme heat directly threaten yields, supply security and the long-term viability of agricultural businesses.

For cooperatives and other types of agricultural-based business, this reality cuts both ways. On the one hand, they must manage rising physical risks. On the other, their position – often owned by or closely tied to farmers – puts them at the center of efforts to build resilience and deliver on the climate commitments made by consumer goods companies downstream. These companies and their brands are under mounting time pressure to hit environmental goals, and they can’t get there without the suppliers closest to production.

Scope 3 emissions – the ones embedded in the commodities produced and traded by cooperatives and other agricultural businesses – account for the lion’s share of the footprint in food and beverage. And while brands are setting ambitious targets, they typically don’t source crops or livestock directly. They depend on cooperatives to translate downstream commitments into upstream action. Some companies are already embedding climate requirements into contracts. Others are offering premiums for verified low-carbon commodities. A few are making climate performance a condition of doing business.

That’s the good news: deliver credible, traceable and verifiable reductions, and sustainability can move from a cost to a revenue driver. But the market for claims is murky, the technical rules are strict, and the window for securing buyer investment is short. Which is why it’s critical to understand the dynamics at play today, and what it takes to move forward with confidence.

Scope 3 moves to the top of the agenda

Despite the fact that scope 3 emissions make up the vast majority of their climate footprint, many food and beverage companies are struggling to deliver meaningful reductions. Operational emissions (scope 1 and 2) have been easier to address through renewable energy, equipment upgrades and process efficiency, but they represent less than 10% of total emissions for most companies. The other 90% lies upstream, embedded in the value chain; addressing these emissions requires supplier partnerships, innovative funding mechanisms, and systems to credibly transfer impacts from the farm gate to the retailer. This puts raw materials suppliers, co-ops and the farmers they represent squarely in the spotlight.

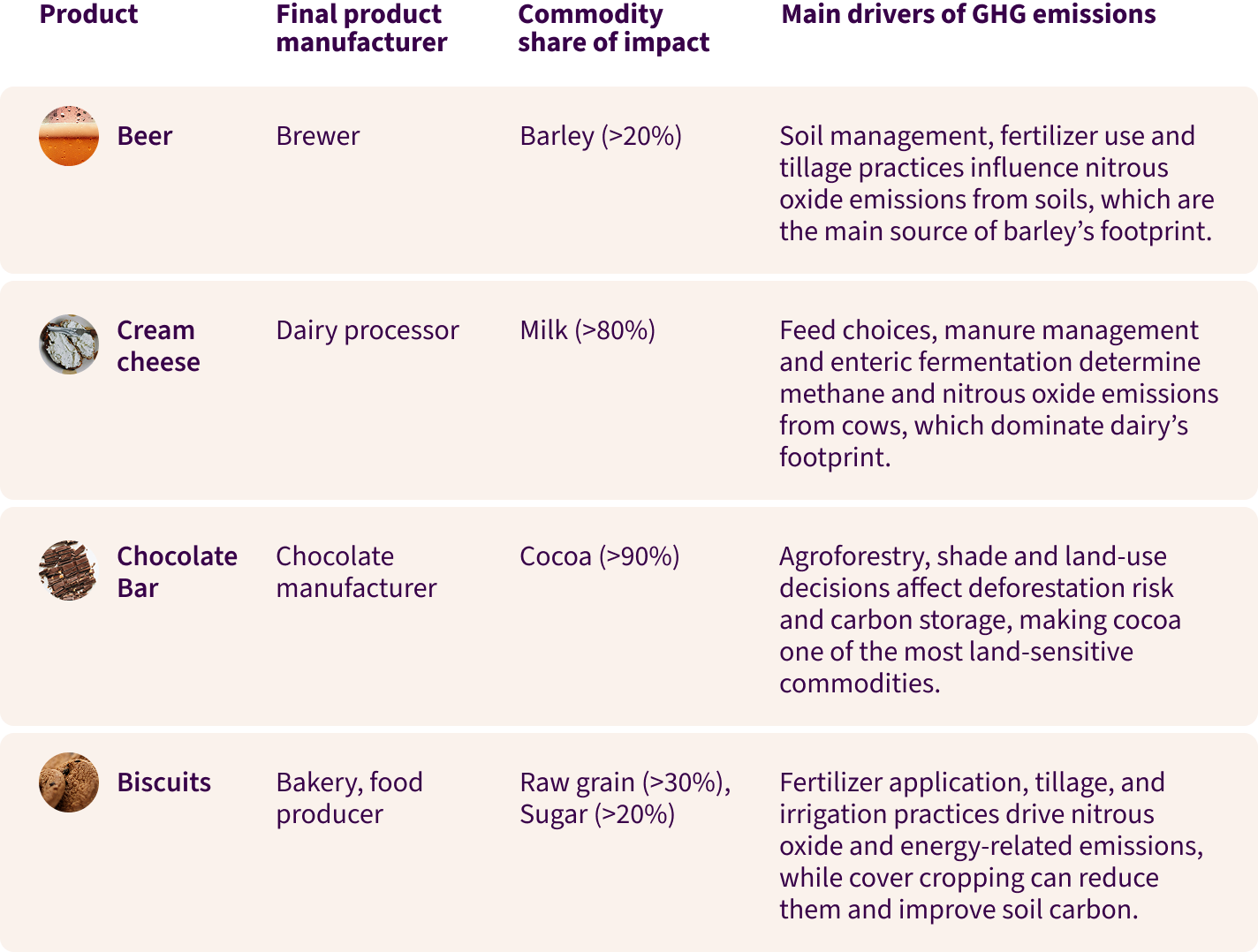

In every category, the pattern is the same. Emissions don’t stop at the factory gate – they flow through the value chain. The table below shows how this plays out across different value chains, and why farming practices are central to driving reductions.

The premium opportunity for verified reductions

Many CPGs set their climate commitments back in 2017 or 2018, with 2030 deadlines that felt comfortably distant. Now, the mid-decade check-in is here, and supplier-driven reductions are only just beginning to show up in the data. Brands with Science Based Targets are discovering that getting verified scope 3 reductions is more complex than anticipated. Premiums for lower-carbon commodities are no longer hypothetical. Those that can move now, credibly and at scale, won’t just secure their place in the supply chains of the future, but they can also get paid for it.

In practice, the premium opportunity looks like this: a raw materials supplier or co-op mobilizes its farmers to implement targeted emissions-reducing practices, measures the climate impact, verifies the reductions, and embeds those verified benefits into the commodity as it moves along the chain. Early pilots across sectors have shown this model is possible. In some supply chains, raw materials providers and co-ops are already embedding emissions data into commodities as they move from farm to buyer, unlocking new commercial value from verified reductions.

Czarnikow’s VIVE Programme offers a leading example of this approach already in action. Designed in partnership with Quantis, VIVE’s Climate Action initiative helps sugar supply chain actors measure and verify emissions reductions, and then associate those verified climate benefits with the sugar as it moves along the chain. This allows food companies to purchase sugar with transparent, science-based emissions data attached, transforming sustainability performance into commercial value.

While shifting practices takes upfront investment, the long-term returns are becoming clearer. Once regenerative practices are scaled, usually after 4-5 years, some pilots show farmers can see a return on investment of 15 to 25 percent , reinforcing that climate action, when done right, can deliver both environmental and economic outcomes. But these economic gains don’t come overnight. To get there, farmers can’t be expected to bear the significant upfront transition costs on their own; brands and buyers need to play a role in de-risking and financing the shift so that long-term value can be realized across the supply chain. transition costs on their own; brands and buyers need to play a role in de-risking and financing the shift so that long-term value can be realized across the supply chain.

Untangling the sustainability claims marketplace

But there’s a catch: the sustainability claims marketplace is, frankly, messy. There’s a little bit of ‘everything and anything’ out there – from solid, science-based programs to those built on questionable assumptions. Agriculture makes it even more complicated. Practices like agroforestry, reduced tillage or cover cropping can deliver real climate benefits, removing carbon from the atmosphere and storing it in soils and biomass. But how those reductions, removals and avoided impacts are measured, attributed and transferred along the value chain makes all the difference. Get it wrong, and a claim can crumble under regulatory review or NGO scrutiny.

And carbon benefits are just one piece of the puzzle. Improvements in land, water, and more efficient input management are also being brought to market – each with its own accounting challenges and scrutiny standards. The Greenhouse Gas Protocol provides the rulebook for scope 3 accounting, but applying it in agriculture involves judgment calls, robust methodologies and technical nuances.

The potential to monetize these environmental attributes adds another layer of complexity. Verified claims are quickly becoming the minimum requirement for market access, even when no price premium is attached. Premiums, meanwhile, remain uneven:

- In B2B markets, some food and beverage companies are starting to pay more for low carbon commodities, particularly where scope 3 reductions are essential to meeting their targets.

- At retail level, the picture looks different. While sustainability can influence shelf space and market share in some regions, willingness to pay more remains limited everywhere.

For co-ops and raw materials suppliers, navigating this landscape is critical: credible claims are quickly becoming non-negotiable, while premiums may only emerge selectively depending on category, geography and buyer strategy. But building the systems and practice changes required to deliver those claims carries real costs. Even where end consumers aren’t yet willing to pay more at retail, the burden cannot fall on co-ops alone. CPG companies will need to share the investment – whether through targeted support, contract terms or partnership models – to ensure the transition is both credible and commercially viable across the value chain.

Why chain of custody is the real bottleneck

Without good farm-level emissions data, the commercial opportunity for verified low carbon products becomes harder to capture. Chain of custody doesn’t create the data – but it does ensure that any data you do have can be transferred along the value chain in a way that is robust and defensible. That starts with having clear visibility over the volumes produced by each participating farm and knowing exactly where those volumes go. When those volumes are linked to verified practice changes and measured impacts, the environmental benefits can move with the commodity as it’s then transformed into an ingredient and, finally, a product – from farm to co-op or raw materials supplier, to brands, to retailers – all without losing credibility. Most supply chains aren’t set up for that level of precision. Building it means investment in systems, training, and sometimes changing procurement practices. But it’s the price of entry to the premium market.

For co-ops or raw materials suppliers looking to establish a chain of custody system, there are three critical considerations:

- Clarity of scope. Define from the outset which commodities, farms and practices the system will cover. This avoids gaps later and ensures that all participants are aligned on the rules. Just as importantly, recognize the realities of your value chain structure. Some commodities, like U.S. corn and soy move through highly aggregated systems with little or no segregation – meaning attribution will depend more on mass balance approaches.

- Data integrity. Put in place processes to verify volumes, trace origin and match product flows with emissions data. This may involve digital recordkeeping, batch coding or integrating with farm management software.

- Alignment with recognized standards. Ensure the approach aligns with widely accepted frameworks – and, in agriculture, that means going beyond the basics. Start with the Greenhouse Gas Protocol and apply its Land Sector and Removals Guidance (LSRG) for consistency in accounting for soil carbon, forestry and other land-use related emissions. Pair this with standards from ISEAL, which provide principles for credible sustainability claims and assurance systems. Together, these frameworks give buyers and auditors confidence that reductions are being tracked and reported credibly across the value chain.

Building a reliable chain of custody is not just a technical exercise – it’s also a relationship and change-management challenge. Farmers, processors and logistics partners need to understand their role in maintaining integrity and be equipped with the tools and training to deliver it. The core requirement is visibility: knowing what volumes are produced, where they move, and how they connect to verified reductions. That can be managed with something as simple as spreadsheets at the start; blockchain or AI aren’t prerequisites. What matters is transparency.

Still, even small gaps can carry big consequences, as errors or inconsistencies in the chain can undermine the value of the verified reductions you’re selling. A missing link, a mismatch between volume and emissions data, or unclear transfer rules can mean the difference between a premium sale and a claim that won’t pass buyer or regulator scrutiny. Getting it right creates a durable commercial advantage; getting it wrong risks credibility and revenue.

It can be done. Arla Foods is showing what this looks like in practice. Through its climate check program, Arla is collecting farm-level data across its 8,500 farmer-owners and feeding it through the cooperative’s supply chain. This allows reductions to be verified, transferred and demonstrated to buyers with confidence – proving that a functioning chain of custody can both unlock premiums and build stronger supply relationships.

Financing verified reductions

As scope 3 expectations become more concrete, the financial dynamics between buyers and suppliers are beginning to shift. Until recently, there was little clarity – or accountability – around who should cover the cost of emissions reductions and removals across the value chain. Now, some consumer goods companies are offering financial support through targeted investments or premiums for verified low-carbon commodities. Others take a firmer stance, treating climate performance as a baseline requirement rather than something they’ll pay extra for.

This shift has real implications for how climate action gets funded. While some buyers still contribute upfront to support transitions, many are now moving toward performance-based models, where suppliers receive a premium only once emissions reductions are verified. This approach is more scalable – but it puts pressure on co-ops, raw materials suppliers and farmers to absorb early costs, which can be a significant barrier without the right financing tools in place.

Procurement teams are increasingly at the center of these decisions. They’re being asked to embed climate performance into contracts, often without the technical grounding to evaluate reduction claims or price them appropriately. Co-ops and raw materials suppliers that can meet this need with a clear, tiered offering – linking levels of verified reductions to differentiated premiums – are more likely to succeed in commercial negotiations. For buyers, these offers reduce complexity. For co-ops and raw materials providers, they open the door to monetizing emissions reductions at scale.

What co-ops and raw materials suppliers can do now

The window is open now, but it won’t stay that way forever. The scope 3 shift is both a challenge and an opening, and those that move first, with speed, credibility and the right partners, will take the commercial and strategic lead. But speed without structure is a risk. For co-ops and raw materials suppliers ready to lead, getting started doesn’t require perfection, but it does require a clear plan.

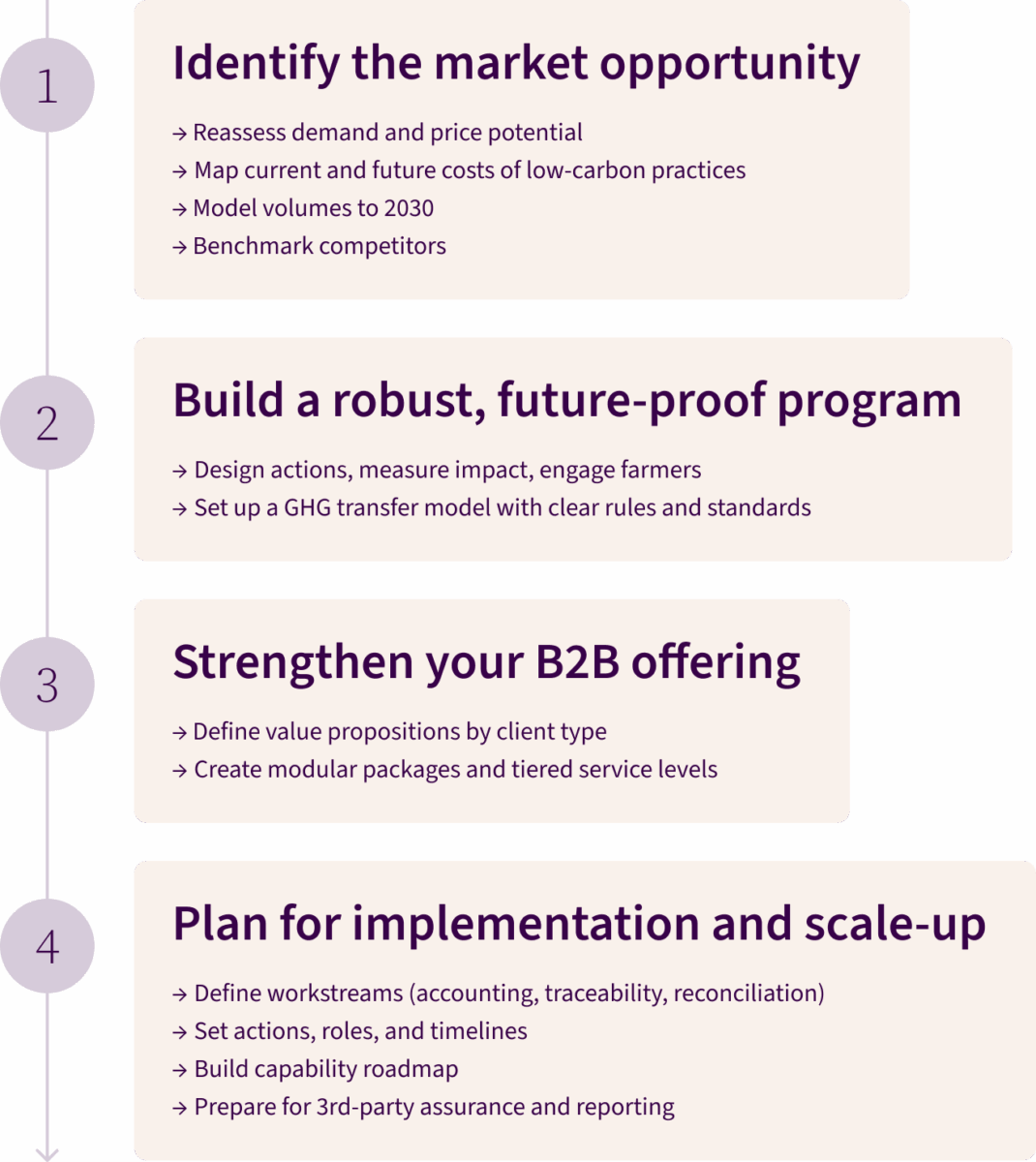

Here’s where to focus first:

With the right foundations in place, co-ops and raw materials suppliers can move from supplier to strategic partner – capturing green premiums, meeting buyer expectations and positioning themselves in the low-carbon supply chains of tomorrow. But credibility matters. A structured, verifiable offer is what turns climate ambition into long-term commercial value.